Former KOC Employee & Minister of Housing shares highlights from his career in service to Kuwait

TKD: You have had a very distinguished career in service to KOC and Kuwait - first through your expertise in the field of oil and gas, and then in the political realm. As a young man, what did you study and why did you want to join KOC?

Al-Sumait: There was no choice for me for KOC to begin with – it was destined to happen. I started school in an area called Qibla, where I attended Muthana Elementary School. I then went to Shamiya Intermediate School before attending Shuwaikh High School, where I graduated in 1964/65. I then had the opportunity to study in the United States on scholarship. At the time, we didn’t have the advisory systems that are in place today that can help Kuwaiti students studying abroad, so there was a steep learning curve. In the beginning, the most important thing for me was to gain control of the English language. In all, I spent five years at university until I graduated in 1971 with a B.S. degree in Geological Engineering. I wanted to continue studying so that I could receive my Master’s Degree, and I arranged to do so and took the required classes. However, I was soon called back to Kuwait, which was around 1972.

I joined the Ministry of Finance when I returned to Kuwait, which was being run by Abdulrahman Al-Ateeqi, who was a friend of the family. I stayed there for two years, and part of my responsibilities included conducting oil inspections in Ahmadi, where I also lived. It was around that time that I was approached by an American oil company, AMINOIL, who asked me if I would be interested in working in America. They had a program set up for me, and when I accepted their offer, they took me to their New York offices where I worked in their international oil marketing division. Initially, they had me working on the telex machine. They would go out for lunch and I would continue working, learning as I went along.

Within a month I was part of the group, but it wasn’t an easy task. I quickly learned that the most important thing was to always use your head, and to never make a commitment to a job or task unless I was absolutely sure about the accuracy of my findings or answer. After another month or so of work, my colleagues were happy with my work and I was taken to Houston, Texas. When I arrived, I was given about 15 books and was told that I had two weeks to finish reading them. The material covered topics related to the geology of the area and the oil industry, and I had nothing to do but read those books and take good notes. Within two weeks, we sat down again together and went over the material. They thought I understood everything I needed to know, so our group then began preparations for a presentation we needed to deliver at the company’s main office. I began working on economic planning studies for areas that were going to be drilled, which involved selecting the appropriate blocks for exploration. Within three months, I learned how to do the calculations, which involved using an early computer – the type that used a punch card and so forth that took a lot of time to do basic processes. We went over our studies and after three more months we selected the three blocks we had analyzed before agreeing it was time to deliver our presentation to the management.

On the day of the presentation, I walked into a room where three or four men from the board of directors were present. It was a nerve-wracking experience, especially when my colleagues told me that I would be delivering the presentation’s opening remarks. This, of course, was a shock to me. I had never delivered a presentation like that before, I didn’t have full command of the language, and I wasn’t sure if I would be able to do it. But, one of my colleagues took me aside and walked me through what needed to be said, so I felt better after that. When my turn came to speak, I faced the board of directors, took a deep breath, and did what had to be done. The reason why I am telling you this story is because that event represented a pivotal moment in my career. It was a very important learning experience for me, and one which I will never forget.

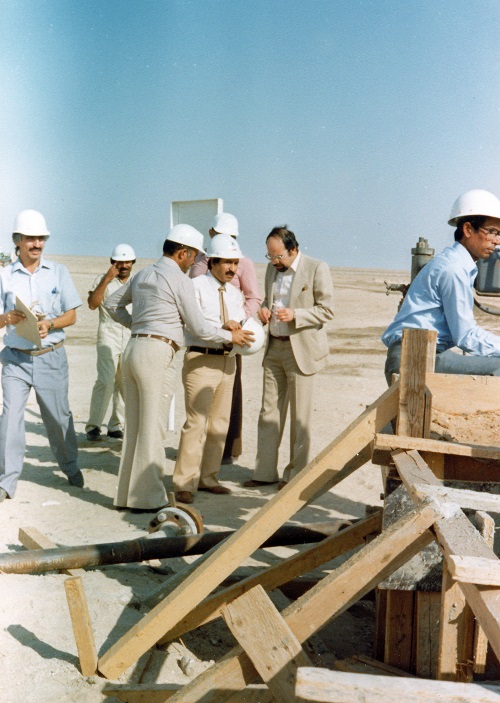

At any rate, I continued to work at AMINOIL for two years before the Minister of Finance spoke to my father and asked why I was working in the United States when my services could be utilized here. “Kuwait needs him,” was what he told my father. Soon after, my father gave me a call and I returned home to Kuwait in 1977, where I immediately joined KOC and was appointed as Superintendent of Local Relations. I asked the head of KOC at the time why I had been appointed to Local Relations – after all, my degree was in Geological Engineering, and I thought I could be used for better purposes elsewhere. He made the case that someone with my expertise was needed at the team, so I stayed on for two years before I became General Superintendent for Production. In my time in that position, I brought up the very important point that KOC was in need of a gas division. I made the case that this was a significant part of the future of petrochemicals, and that KOC’s gas section should be expanded, which of course it eventually was.

Eventually I was transferred to Wafra where I spent a year and a half representing KOC, where we did a very good job in our work with Saudi Arabia on a number of projects, and I also became close friends with the Governor of Khafji. At some point in my career in Wafra, I received a call saying that the Prime Minister, His Highness Sheikha Saad, may Allah rest his soul, wanted to meet with me. I met with the Prime Minister, and our first discussion touched on oil - how we explored for it, how we drilled for it, and how it was produced. To me, the logical correlation was that the Prime Minister was considering me for the role of Minister of Oil; however, just before the announcement of the Cabinet, I received a call informing me that I would be the Minister of Public Works. Naturally, this surprised me, and I let them know that I was not a civil engineer and that I could not help the government in this way. I told them that I had been trained for the oil industry and that this was where my experience was. The message was passed along to H.H. Sheikh Saad, and later on that night, I turned on the radio and learned that I had been appointed as Minister of Housing.

After learning about the appointment, I requested a meeting with H.H. Sheikh Saad. When I met with him, he said to me, “Sumait, sit down.” His method, of course, was nice and courteous, but also a bit scary. In our discussion, I asked him what the logic was behind appointing me as Minister of Housing. I let him know that my entire career had been devoted to the oil and gas world and that I had experience in this field in Kuwait, working with the Saudis, in Europe, and in the United States. I told him that my experience working in the United States could lend itself greatly to my work in Kuwait, where I could apply the system I had learned there to here. He smiled and said, “That’s what’s bothering you?” I said, “Yes.” And then he asked me, “Didn’t you run for election in 1980 and lose? Why did you lose? You lost because nobody knew who you were. Take this position, be the Minister of Housing, work with Kuwaitis, and everyone will know you. Then, run for election, and you will see the positive outcome. Besides, don’t worry, I will make sure you are on the Supreme Petroleum Council.”

I began my work in the government shortly after that, but as you know, the time of the invasion came. In the early days of the invasion, we had no tools to communicate with Kuwaitis inside Kuwait – at first we didn’t have access to TV, radio, nothing. Within the Cabinet, we had one minister that spoke French, one that spoke English, and I also was able to conduct our communications in English. We had to think of something fast. In Saudi Arabia, we managed to organize our efforts through a small station in Khafji and send a short message to Kuwait. I was the first one to say “Hello, Kuwait.” We broadcasted our message inside Kuwait and let everyone know that H.H. the Amir was safe, that the Cabinet was still intact, and that we were doing everything in our power to begin making things right. Sheikh Sabah Al-Khalid would come to us with a tape recorder so that we could read our messages to the Kuwaiti people inside occupied Kuwait. As you can imagine, in those first days it was not easy to control our emotions when we spoke as we repeated our message that H.H. the Amir and H.H. the Prime Minister were safe. We would issue patriotic messages to those inside Kuwait and we let them know that we were doing everything we could. However, this of course was not easy for us – it was very difficult to imagine that we were without a country. This idea that we had lost something as dear to us as Kuwait really hurt our souls. But we had to press on, so we assumed the formation of our information battle.

We had to project a public image for the Kuwaiti government, and we worked tirelessly in this regard. In Saudi Arabia, I met with journalists from newspapers and magazines around the world, and I also represented H.H. the Amir in Asia and Africa. I would travel to various countries and present the foreign dignitaries with letters from H.H. the Amir. I then would go to the various newspapers or TV stations to discuss the situation in Kuwait and make the case for my country. We realized very quickly that we had to intensify our efforts, because in the beginning, the Iraqi media control was very strong. We really worked tirelessly to make the case for Kuwait, and I believe our efforts truly made a difference in creating a good public appearance for the government. At the time, H.H. the Amir was pleased with my work, and one day he told me that he was going to send me to Africa to meet with leaders there, such as Mugabe, because a number of those countries were on the General Council of the United Nations. It must be said that the Egyptian ambassadors I met along the way were very helpful and showed us great support in this cause. In terms of the interviews and statements we made during the invasion, we were of course angry, but it was very important to not show that anger. It was very important that we remained level-headed, calm, and collected. With time, and after conducting many interviews one after the other, it became easier for us to discuss our case with the newspaper, magazine, and TV reporters.

After the liberation of Kuwait, the national sentiment and political situation was a bit fragile. The Kuwaitis who remained inside the country during the invasion, those who were scared, tortured, lost their loved ones, some of them could not understand why we had left Kuwait at the beginning of the invasion, and they wanted to change the Cabinet and make political changes. To alleviate these feelings, the other Ministers and I approached H.H. Sheikh Saad and told him that we would all resign from our positions and form a new committee to alleviate the political discord that existed. This idea was very much appreciated by H.H. the Amir and H.H. the Prime Minsiter, and I then was appointed to the Board of the Housing Committee, then I became Member of the Board of KPC, then I became a Member of the Board for the Supreme Council of Planning, a position I held until last year.

In brief, this has been a summary of my progress in life, and I believe we covered quite a few of the highlights despite that being your first question!

TKD: What were your feelings at the time of the invasion? Everyone fought in their own way, but was there ever a time where you felt there was no hope? What kept you going?

Al-Sumait: That’s a very good and important question. My kids were young, very young at the time. The night before the invasion, we had gone downstairs to eat dinner, and I told everyone that I had to go to sleep early because H.H. Sheikh Saad had returned from Saudi Arabia and we had a very important meeting early in the morning to decide what to do with the developing situation. When the invasion happened, I received a call, but it went unanswered. It was then that H.H. the Amir and H.H. the Prime Minister were taken to Wafra or Saudi Arabia. When I woke up in the morning, I heard jet planes roaring. I got a call from a friend in the United States, and he asked, “What’s going on? I’ve heard the Iraqis are inside Kuwait.” And then I opened my windows and I saw there were helicopters and soldiers outside. Then the Minister of Oil called me. He was worried because at the previous meeting of OPEC, he had a conflict with the Iraqi Minister of Oil. He said, “If they catch me, I’m finished.” I tried making calls to various government offices, but there was no answer. I called an official in Ahmadi, and when he answered, he wasn’t as lively and social as he usually is. I told him who I was and he answered with short, one word answers. I asked him, “Are they standing next to you?” He said, “Yes.” At this point our concern gravitated around the safety of our children and family, so we gathered everyone together and drove to our chalet in Zour. I then called the Minister of Health, who was in the hospital. I asked him if the Iraqis were there, and he told me they were. I asked him what he was waiting for, and that he should escape in an ambulance. There was a car waiting for him somewhere, and when he arrived to our location we all had a meal together and found out the government was in Khafji, so we went to Khafji.

The feeling that we were without a country was a very difficult one to process. I remember when we were in Saudi Arabia, I was with some of Kuwait’s senior officials and we saw a street sweeper cleaning the street. One of us said, “You know what the difference between us and that man is? He has a country. We don’t.” We all felt our hearts drop. It was a very scary thing to think about. In the days that followed, there was no clear answer at the beginning – we didn’t know what the future held. After a couple months, the UN released the fund for Kuwait, and I was part of the committee that overlooked caring for the Kuwaitis in exile. We made a tour of the Arab countries and England, places where Kuwaitis were staying. Of course, everyone wanted answers, but all we could do was offer the financial assistance and ask them to pray while we all worked on liberating Kuwait.

One of the first encouraging signs I saw at that time was when I spoke to the US Ambassador in Saudi Arabia. He asked me, “If you return to Kuwait, will you make a dinner for me in your diwaniya?” I told him I’d make a dinner for him every week if that were the case! He said, “OK, inshallah everything will be alright.” That was the first encouraging sign, and gradually we began to discover what was going on. Two weeks before the liberation, the other Ministers and I were taken to a very secret meeting with a high-ranking US military officer. H.H. Sheikh Saad was also present. The officer had a map of Kuwait and Iraq, and he began detailing the preparations that were being made. He told us they were expecting the Iraqis to do such and such, so the US would do this or that, he told us the US forces would arrive on the beach through the sea and so forth. Of course, these details were not true, as a sea invasion never occurred, but I believe this was all done by design, which was a brilliant strategy executed by the Americans, because two hours later, when I arrived home, my wife’s sister was talking to me excitedly about how the Americans were preparing to liberate Kuwait – she knew the details of the meeting! I asked her how she knew this information; obviously someone at the meeting disclosed the details to his wife. But I believe the plan worked, and I understand why the Americans did this. They assumed someone would leak the “secret” plan and that it would reach the Iraqis, and it did. The Iraqis were thrown off, because of course the war started very differently.

To answer your initial question: Yes, there was a time when you just sat by the radio to listen to Voice of America or the BBC to hear the commentaries and learn about what was going on and what the expectations were. What did Saddam say, what did Baker say, and of course we had CNN coming to Saudi Arabia, and that was a very good opportunity for us. I was one of three ministers willing to speak on camera, and we had a very good interview. Luckily things went OK. But, to answer your question, there was a time when we thought we were without a country, yes.

TKD: What should Kuwait take away from the whole experience of the invasion?

Al-Sumait: To be a small nation with abundant natural resources and high levels of education is a great thing. We are truly blessed. But the government system has spoiled many Kuwaitis. We have been babied to the point where we don’t use our heads, to the point where we are not independent. When we returned to Kuwait after the invasion, we said we had to do something about this situation, but the government, out of concern for the citizens, did not want to cause any further friction. Despite that, we produced a very good plan for Kuwait’s future, but unfortunately, when the new Cabinet came in, issues of politics began to arise, with parliamentary roadblocks, disagreements, and conflicts springing up that prevented important progress from happening. When I interact with some members of the public, I find it very discouraging to discover the mentality that exists with some citizens. I’m speaking now of individuals that demand more salary, but who may only go to the office once or twice a week. Unfortunately, very few people teach their children about important issues like the merit of hard work and the value of money and saving.

TKD: If you could offer a solution for the country, what would it be?

Al-Sumait: There is no simple answer for this question. In Kuwait, we have issues of tribalism and division among the population that must be overcome. The issue is that even today, in our modern world, many continue to fall into this trap. At the heart of it, we are all Kuwaiti, and we need people who can think outside of this box, and we need a system that cuts off the energy supply for this type of mentality that unfortunately exists.

The other issue is that the government is not in a position to create disorder in Kuwait. The simple issue of raising the price of electricity caused an intense public debate. But go to Doha and see the 18 inch crude pipeline that is the fuel for our energy and water plants. The amount of oil, our natural resource which should be exported, that is required for domestic energy and water production is staggering. But the citizens don’t know the true cost. Instead, they wash their cars and driveways with water every day and leave the lights on at all hours. If we only knew the true cost of these wasteful activities, perhaps we would be less wasteful, but this is how Kuwaitis are raised. As an example, look at what happened when the price of oil fell. No wealth lasts forever, and it is wrong to think you can live like a king for the rest of your life. Even kings don’t live like kings all their lives. This is what intellectuals and young people in Kuwait should be discussing. However, in regard to your question, no single answer exists.

TKD: How hopeful are you for Kuwait’s future and what is your advice to young Kuwaitis?

Al-Sumait: There is always hope. There is always hope when you make the proper plans for something and take the time to cultivate that which you wish to see grow. For example, we must provide our children with proper education and we must teach them ethics so that they can be productive members of society. Something which I feel is important is that we should also teach our children to manage their finances properly – we see too many individuals today spending money they do not have and taking loans for things they do not need. When my children started their careers, I always taught them to divide their salary in three parts, a third of which is for them to spend as they please, a third of which is to be saved for contingency expenses, and a third that must be saved. They quickly found out they could afford the things they needed and save money for their future. It all depends on what we teach our children. With education and proper guidance, we can hope for the best in most cases.

TKD: Would you say the highlight of your career was serving your country during the invasion?

Al-Sumait: I think that would be a fair assessment. Personally, I feel the work I did after the invasion was also very important for the country. I would receive calls from H.H. the Amir and H.H. the Crown Prince, and they would tell me that they did not forget what I did for the country, and that they appreciated the work I did in service to Kuwait. To me, that was a rewarding experience.

My time in the United States also played an important part in my career. I learned a lot by working there, and not only in the educational sense. I learned to be pragmatic and practical, and appreciate the value of hard work. When I became Minister, I showed up at my job at 7 AM sharp, but I was surprised that nobody was there. This has always troubled me. If I have a job, I aim to do the job to the best of my ability. Work, and work with a purpose, helps provide meaning to the individual, and it is especially important when done in service to your country. At KOC, I learned the importance of structure, organization, and punctuality, and I tried to apply these principles to the government departments I presided over. I’ve lived my life working, and when I worked in Wafra, showing up at my office at 6:45 AM, I was happy.

Some of the systems and positions we have in Kuwait are obsolete, which is why it is hard to accomplish important goals, unfortunately. However, I am not disappointed, because I believe things will change. We may need an awakening, however. We have to realize this is not a dream, it’s real life, and life is tough and nothing will last forever. Look at history: kingdoms rise and fall.

TKD: What is your advice to the younger generation?

Al-Sumait: After more than 50 years since the production of oil in Kuwait, we unfortunately still do not have the Kuwaiti expertise that should exist – technically or economically. My advice is that we have to take the name of Kuwait and KOC, the company that introduced Kuwait to the world, and we have to work loyally for the benefit of our country. To this day, I am loyal more than anything to KOC, and I believe we have to dedicate our lives to our work. If you are loyal to your job, and if you are loyal to your company, then I believe you are loyal to Kuwait.

*